I'm converting my iTuro workshops into a series of blog posts.

I made my first series of educational videos when I joined the UP Gawad Pangulo competition for progressive teaching and learning. Since I used project-based learning as a strategy, the videos were not lectures per se but a guide on approaching the driving question for the week.

Every week, students answer the driving question by submitting a "project," an artifact of learning. The project makes the learning visible to me as their teacher.

I used the video format to explain the driving question, suggest approaches to answer it, and highlight recommended readings.

Check out this reference - CBE Life Sci Educ. 2016 Winter; 15(4): es6. doi: 10.1187/cbe.16-03-0125 Brame says for educators to consider these three elements for video design: cognitive load, student engagement and active learning.

Since I wasn’t actually using the video to deliver content in my graduate class (the students need to read the article(s) in the reference list, perhaps the cognitive load isn’t too much (or at least I hope so). But what is cognitive load?

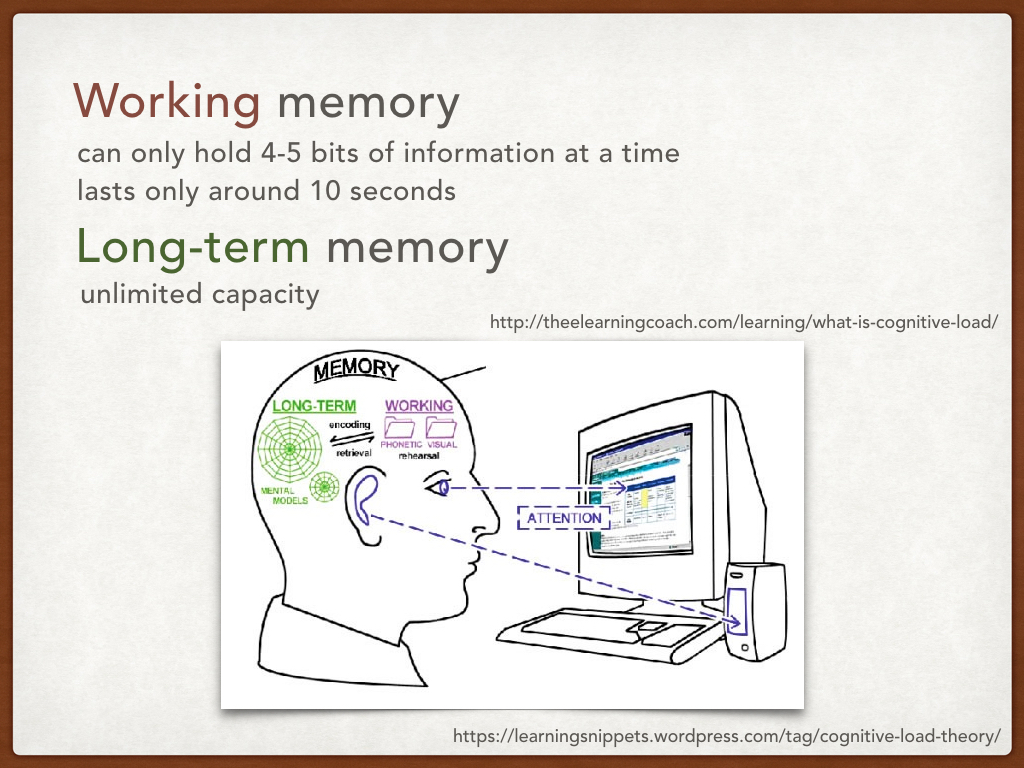

Information in long-term memory is stored as schemas. Schemas are built in working memory and then integrated into long-term memory. When we need that information again, the schema must be loaded into the working memory from long-term memory. Ah, kaya ba "stock" knowledge or minsan nagiging "stuck" knowledge?

Cognitive load is not necessarily bad as it can be intrinsic (ex. physics is difficult for me to understand) and germane (load for processing information) but as teachers we can try to decrease EXTRANEOUS load (you know, like Death by Powerpoint).

For instruction to be effective, cognitive load must be less than the working memory capacity. Say what?! But, but ... the previous slide said, we can only hold 4 to 5 bits of information for around 10 seconds in working memory?

If we consider teachers to be experts, their job is to help their students construct schemas. This facilitates the back and forth between working and long-term memory. But that would mean that a teacher’s memory looks like the diagram below. I’m not sure mine looks like that!

And so perhaps, instead of using videos to deliver what we used to lecture in the classroom, we can help learners think about how they understand the subject matter.

The working memory has two channels: visual-pictorial and auditory-verbal. Cynthia Brame reminds us that –

Although each channel has limited capacity, the use of the two channels can facilitate the integration of new information into existing cognitive structures. Using both channels maximizes working memory’s capacity—but either channel can be overwhelmed by high cognitive load. Thus, design strategies that manage the cognitive load for both channels in multimedia learning materials promise to enhance learning.

CBE Life Sci Educ. 2016 Winter; 15(4): es6. doi: 10.1187/cbe.16-03-0125

Thinking about the visual-pictorial and auditory-verbal channels also got me asking, why does it have to be a video? What are we imparting in the video that the students cannot access by reading our handouts or the books/journal articles in our reading lists? When we are able to answer that, then THAT (whatever it is) should be on the video. Perhaps it will be THAT which reduces cognitive load for our students.